The Darker Side of Icelandic History

In 1596, as the executioner raised his axe at Laugarbrekkuþing, Iceland’s most notorious killer, Axlar-Björn, faced his final moments—his body soon to be hacked apart and displayed on stakes as a warning to others. Three centuries later, an Icelandic woman, Arndís Jónsdóttir, was sentenced to a lifetime of forced labor—not for killing, but for giving […] The post The Darker Side of Icelandic History appeared first on Your Friend in Reykjavik.

In 1596, as the executioner raised his axe at Laugarbrekkuþing, Iceland’s most notorious killer, Axlar-Björn, faced his final moments—his body soon to be hacked apart and displayed on stakes as a warning to others. Three centuries later, an Icelandic woman, Arndís Jónsdóttir, was sentenced to a lifetime of forced labor—not for killing, but for giving birth to eight children out of wedlock. These are just two of the many brutal stories hidden within Iceland’s legal history.

Iceland is often associated with breathtaking landscapes, ancient sagas, and a deep-rooted literary tradition. However, the darker side of Icelandic history tells a different story—one of gruesome murders, brutal legal codes, and tragic miscarriages of justice. While many view Iceland’s past as a tale of resilience and survival, its legal and criminal history reveals a far more complex and often chilling reality.

If you’re visiting Iceland and fascinated by its eerie past, consider joining The Reykjavík Folklore Tour, where history and folklore intertwine in chilling tales of outlaws, hauntings, and Iceland’s darkest legends.

Axlar-Björn – Iceland’s Only Known Serial Killer

Few figures stand out more in the darker side of Icelandic history than Axlar-Björn, the island’s only known serial killer. His story is filled with legend, but the core of it remains a chilling reminder of how justice was served in 16th-century Iceland.

Björn Pétursson (c. 1555–1596), got his nickname from Öxl, the farm where he lived in Breiðavík, Snæfellsnes, near Búðir. The most detailed written account of his crimes comes from Reverend Sveinn Níelsson, who based his work on an “old and wise local man.” This version became the foundation for Jón Árnason’s collection of Icelandic Folk Tales, though many elements are clearly exaggerated.

Early Life and Murders

Björn was the youngest of three children and worked as a farmhand for Ormur, a wealthy landowner. After Ormur’s death, his son Guðmundur gifted him the Öxl farm, where Björn lived with his wife, Þórdís Ólafsdóttir.

Authorities unearthed multiple bodies at Öxl. Björn claimed he had simply reburied old remains—but as the bodies piled up, so did the suspicions.

According to Björn, he committed his first murder at the age of fourteen, killing a man in a sheep shed. The true number of victims remains uncertain, but it is believed that most were travellers or farmhands seeking work. He lured them to his farm, robbed them of their clothes, money, and horses, and then killed them—some say with an axe, others claim he drowned his victims.

Annals record three different versions of how he was eventually caught:

- Ballarárannáll states that a man from Miklaholtshreppur went missing. His brother later recognised his cloak on Björn, leading to his arrest.

- Sjávarborgarannáll tells of a young man and his sister who arrived at Öxl. When they were separated, he heard his sister screaming. He hid in a barn drain, escaped, and later exposed Björn’s crimes.

- Setbergsannáll claims that a travelling woman with three children stopped at Öxl. Björn lured the children away one by one and murdered them, but the mother escaped and reported him.

The Setbergs Annals also state that Björn admitted to killing for wealth but sometimes murdered the poor as well.

Arrest and Execution

Axlar-Björn was arrested in 1596 and quickly confessed to nine murders. However, discovering additional human remains at his farm raised further suspicions. When questioned, he claimed he had merely relocated bones he had found rather than bringing them to a church burial site.

He was sentenced to death at Laugarbrekkuþing, where, according to some accounts, he was beaten with sledgehammers, then beheaded and dismembered, with his body parts displayed on stakes. However, court records only state that he was executed according to Icelandic law, making the claims of torture uncertain.

Þórdís and Their Descendants

The Setbergs Annals implicate Björn’s wife, Þórdís, in his crimes, stating:

“When he lacked strength, his wife assisted him. She strangled victims with a rope or her own scarf and sometimes knocked them unconscious with a sledgehammer.” (Ann.IV.73-4)

Despite these accusations, Þórdís was spared execution because she was pregnant. After giving birth, she was sentenced to three floggings instead.

Their son, Sveinn “Skotti” Björnsson, was reportedly born after Björn’s execution. He became a vagrant and criminal, eventually being hanged in 1648 for an attempted rape in Rauðsdalur, Barðaströnd. His own son, Gísli “Hrókur” Sveinsson, followed in his footsteps and was executed in 1657 for robbery.

While Axlar-Björn remains Iceland’s most infamous individual murderer, the island’s history also bears witness to mass killings, such as the brutal massacre of Basque whalers in the 17th century.

The Slaying of the Spaniards (Spánverjavígin)

The Slaying of the Spaniards, also known as the Spanish Killings (Spánverjavígin), refers to events that took place in 1615 in the Westfjords of Iceland, when dozens of Basque whalers were killed following conflicts with local Icelanders. It is considered one of the last massacres in Icelandic history.

Background

Basque whalers, originating from both the Spanish and French Basque Country, had been active in Newfoundland since the 16th century, where they helped establish the world’s first large-scale whaling industry. By the early 17th century, they had expanded their operations to Icelandic waters, setting up whaling stations along the coast.

In 1615, three Basque whaling ships arrived off Strandir and set up camp in Reykjarfjörður, where they rendered whale blubber and traded goods with local Icelanders. Initially, relations were amicable, and trade between the two groups flourished. However, that summer, a royal decree was read at the Alþingi, banning all foreign whaling in Icelandic waters. The Basques likely heard about this ruling, causing them to become more cautious.

As autumn approached, the whalers began preparing for their return journey, but on 21 September, a violent storm wrecked all three of their ships. Of the 86 crew members, three drowned, while 83 survived. Stranded and left with almost no supplies, the Basques attempted to secure shelter and food. Some Icelanders sympathised with them and suggested they split into smaller groups to increase their chances of survival. Others pointed them toward a small boat in Dynjandi, Leirufjörður, though it was unseaworthy for crossing the ocean. The whalers rowed north past Hornstrandir and into Ísafjarðardjúp, hoping to find a way home.

Escalation and Conflict

After seizing the boat at Leirufjörður, the Basques split into three groups:

- 51 men from Esteban de Telleria and Pedro de Aguirre’s crews took the boat and sailed south along the Westfjords.

- Martín de Villafranca and 17 men settled on Æðey.

- The remaining 14 men initially rowed to Bolungarvík, then moved to Dýrafjörður, where they stole dried fish and salt from a merchant’s store in Þingeyri and camped in seaside huts at Fjallaskagi.

On the night of 5 October, local Icelanders raided the sleeping Basques at Fjallaskagi, killing all but one, a young boy who managed to hide and later warned his countrymen when their boat passed by. The bodies were stripped and thrown into the sea. Upon hearing of the attack, the remaining Basques sailed south to Patreksfjörður, where they broke into the Danish trading house at Vatneyri, gathering supplies to survive the winter.

The Massacre

Ari Magnússon and the Legal Verdict

The killings were orchestrated by Ari Magnússon of Ögur (1571–1652), the sheriff of the Westfjords, known for his strict and authoritarian nature. He was one of the most powerful and wealthy men in Iceland at the time, serving as sheriff of both Barðastrandarsýsla, Ísafjarðarsýsla, and Strandasýsla while also acting as the royal agent for crown lands in the region.

Ari came from an influential family—his father, Magnús Jónsson prúði, was sheriff of Bær at Rauðasandur, and his grandfather, Eggert Hannesson, was a lawman. Ari was highly educated, having spent nine years studying in Hamburg before returning to Iceland. He was described as tall, strong, and imposing in appearance, and his reputation for ruthlessness was well known.

When Ari learned of the Dýrafjörður attack, he sought to justify further action legally. He issued a legal ruling that declared the Basques to be outlaws (réttdræpir óbótamenn), meaning they could be killed without consequence.

Final Attacks

With 50 armed men, Ari set out for Æðey, but due to bad weather, they were unable to act until 14 October. By then, only five Basques remained on Æðey, while the others were at Sandeyri, butchering a beached whale.

The Icelanders killed the five Basques in Æðey, then moved to Sandeyri. There, they offered Captain Villafranca and his men safe passage if they surrendered their weapons. Trusting the offer, the Basques complied—but as soon as Villafranca stepped outside, he was attacked with an axe. Though wounded, he attempted to escape into the sea but was stoned from boats, dragged ashore, and brutally executed.

The remaining Basques fought desperately, but were systematically overpowered. It is said that Ari’s 16-year-old son, Magnús, personally shot and killed several of them, and the bodies were stripped and mutilated.

Final Pursuit

The surviving Basques at Vatneyri attempted to fish and trade for food, and some locals secretly aided them. Notably, Ari’s own mother, Ragnheiður Eggertsdóttir, was said to have treated them with kindness.

In January 1616, Ari gathered 100 men to hunt down the remaining Basques, but due to severe weather, he could not reach Vatneyri. He did, however, ambush some Basques in Tálknafjörður, killing one and wounding another.

The remaining Basques remained in hiding through the winter, but when an English fishing vessel appeared in spring, they rowed out, seized the ship, and escaped Iceland, never to be heard from again.

Legacy and Commemoration

Jón Guðmundsson the Learned (1574–1658) later wrote A True Account of Spanish Men’s Shipwrecks and Slayings, strongly condemning the killings and describing them as unjust and dishonourable. Wanting no part in the massacre, Jón fled to Snæfellsnes.

Four centuries later, in 2015, descendants of both victims and perpetrators gathered in Hólmavík to commemorate the tragedy. Xabier Irujo, related to the slain Basque whalers, and Magnús Raffnson, linked to those who took part in the killings, unveiled a memorial together. The ceremony included dignitaries from both Iceland and the Basque Country, and the district commissioner formally revoked the 1615 decree that had made Basques outlaws in Iceland.

The Basque–Icelandic Pidgin: A Forgotten Trade Language

In the 17th century, Basque whalers and Icelandic locals developed a simplified trade language to communicate. Known as the Basque–Icelandic pidgin (Euskoislandiera, Basknesk-íslenskt blendingsmál), it combined Basque, Germanic, and Romance languages and is one of the few recorded pidgins based on Basque.

Origins and Documentation

Basque whalers frequented Icelandic waters by 1600, hunting whales and trading with locals. While some believe the pidgin developed in Iceland’s Westfjords, its mix of Dutch, English, French, German, and Spanish suggests broader influences.

Surviving records include:

- Vocabula Gallica (17th century, 517 words)

- Vocabula Biscaica (18th century, 229 words)

These glossaries, discovered in Copenhagen and later studied by Dutch scholar Nicolaas Gerard Hendrik Deen, provide insight into this rare linguistic blend. A fourth glossary, found at Harvard in 2008, revealed additional phrases.

Examples of Pidgin Phrases

The pidgin reversed Basque word order and borrowed elements from other languages:

- Presenta for mi → Give me (Gefðu mér)

- Trucka cammisola → Buy a sweater (Kauptu peysu)

- Christ Maria presenta for mi balia, for mi, presenta for ju bustana → If Christ and Mary give me a whale, I will give you the tail (Gefi Kristur og María mér hval, skal ég gefa þér sporðinn)

Not all exchanges were friendly—some phrases reflect hostility between Basques and Icelanders:

- Sickutta Samaria →Go f** a horse* ( Serda merina)

- Gianzu caca → Eat s** (Jettu skýt)

- Jet sat → Kiss my ass (Kuss þu á rass)

Though now extinct, this maritime pidgin remains an intriguing linguistic curiosity, reflecting an era of trade, conflict, and cultural exchange in Iceland’s history.

Arnes Pálsson – One of Iceland’s Most Notorious Outlaws

In 1763, the famous outlaw couple, Fjalla-Eyvindur and Halla, were captured in Strandasýsla and placed under the custody of Sheriff Halldór Jakobsson at Fell. According to local folklore, during their arrest, another fugitive escaped—supposedly Arnes Pálsson. However, historical records contradict this, as Arnes was freely moving about the region at the time of their capture, openly using his real name. This was a bold move, considering he had been declared an outlaw and fugitive by Alþingi years earlier.

Arnes’ Capture and Trial

Despite the uncertainty surrounding his connection to Eyvindur and Halla, Arnes knew rumors were circulating about him and sought written statements from local farmers in Strandir to confirm his good character. In 1763, twenty men from Árneshreppur signed a testimony on his behalf, describing him in a favorable light.

However, his freedom was short-lived. By 1765, Arnes was arrested and transferred into the custody of Sheriff Jón Jónsson in Strandasýsla. This was recorded in Alþingi’s trial documents, which noted:

“As for the delinquent Arnes Pálsson, the sheriff has confirmed that he has handed over the arrested man to the acting sheriff of Strandasýsla, Jón Jónsson, and is thereby freed from further responsibility in the matter.”

Although Arnes had long been rumored to be living as an outlaw, the official charges against him were for theft, particularly of sheep and money. At his trial in Esjuberg on 17 June 1765, the judge, Sheriff Guðmundur Runólfsson, presided over the case.

The Verdict and Sentence

Although none of the stolen goods were recovered, Arnes confessed to grand theft, which made his conviction inevitable. The court’s ruling was severe:

“Even though none of the stolen items—neither money nor livestock—could be produced before this court, the ongoing confessions of the delinquent make it clear that he is guilty of grand theft. For this crime, the signed ruling is as follows: Arnes Pálsson shall be whipped and branded on the forehead, and he shall spend the rest of his life in chains in the Icelandic prison.”

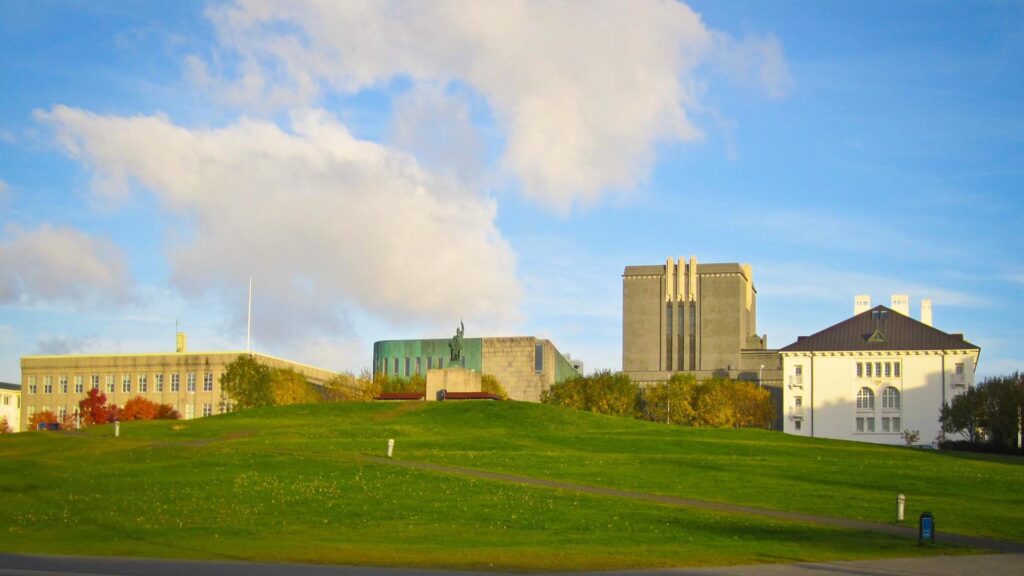

However, a royal decree issued on 11 April 1766 altered his sentence, allowing him to avoid branding. This meant that his punishment was slightly reduced while he would still be imprisoned for life. After years of evasion and outlaw life, Arnes’ time as a free man had come to an end, and he was transported to the prison at Arnarhóll in Reykjavík—the same site that today houses Iceland’s government offices.

Prison Life at Arnarhóll

When Arnes arrived at the national prison on 2 July 1766, Reykjavík was still a small settlement, with most of its houses clustered around Grjótaþorp and Aðalstræti. The prison, a large stone building at the southwest corner of Arnarhóll, was still under construction, only being fully completed in 1771.

The prison conditions were grim. Food shortages, overcrowding, and disease were common. The inmates were expected to perform labor, but the prison lacked organized work programs, leading to idle and restless prisoners. Some were sent to work in agriculture or fishing, but lack of supervision made escape attempts frequent.

Despite his criminal past, Arnes proved to be a master manipulator. He managed to ingratiate himself with the prison authorities, and by 1786, he was officially appointed as the prison’s doorkeeper—a trusted position that gave him more freedom and privileges than most inmates. In the prison records, it was noted that he was:

“The most reliable and suitable man available.”

In addition to this, he was excused from hard labor and tasked with teaching Christianity to his fellow prisoners. He received a small salary for this role, as well as other perks, which made his life in prison far more tolerable than that of his fellow inmates.

Complaints Against Arnes

Despite his privileged status, Arnes was not well liked by the other prisoners. In October 1787, a group of inmates filed a formal complaint against him, claiming that he was abusing his power. In their statement, they alleged that:

“He has threatened to cut off our heads and throw us into hell. He has beaten fellow prisoners bloody, threatened to kill them, and constantly terrorizes us. We live in fear for our lives every night and day.”

Despite these serious accusations, prison authorities defended Arnes, and he retained his position. However, his teaching duties were taken away, and a local pastor was instead assigned to provide religious instruction to the inmates.

Scandals and Illicit Affairs

During his time in prison, Arnes fathered at least three children. The most well-documented cases involve Arndís Jónsdóttir, a young woman imprisoned for having multiple children out of wedlock.

- In 1772, she gave birth to a child fathered by Arnes while in prison.

- In 1774, she gave birth again, but this time Arnes denied paternity.

Despite these incidents, prison officials largely ignored these relationships, as immorality within the prison was not considered a crime requiring additional punishment.

After her release in 1775, Arndís continued to have children, ultimately having nine illegitimate births. She was eventually sentenced to exile in Copenhagen, but was saved from deportation when a wealthy widower married her, securing her freedom from further punishment.

Final Years and Release

By 1792, Arnes was nearly 80 years old, physically weak and mentally deteriorating. Recognizing his frailty, Danish authorities granted him release on 27 January 1792, after 26 years of imprisonment.

For the next several years, he lived as a pauper, first in Grjótaþorp, before being sent to Engey, where he died on 7 September 1805, at the age of 86. He was buried in the cemetery at Suðurgata.

The Trials of Arndís Jónsdóttir

Among the many figures who passed through Iceland’s courts in the 18th century, few left behind a record as extensive as Arndís Jónsdóttir. Over the course of her life, she was sentenced to exile twice, imprisoned twice, condemned to death once, and ultimately ordered to spend the rest of her days in forced labor. Her case was deliberated by three sheriffs, the High Court, the governor, the stiftamtmann, the Danish judicial authorities, and even the king himself.

Her story, later recorded by Guðni Jónsson, earned her the name Barna-Arndís (“Childbearing Arndís”), a reference to the eight children she bore outside of wedlock.

Though her name appeared frequently in legal records, little is known of her own voice, her character, or her daily life, save for what was documented in court proceedings. The authorities pursued her relentlessly, though the records do not suggest she ever harmed another person.

A Life Marked by Legal Troubles

Arndís was born in 1745 at Gamla-Hraun on Eyrarbakki. In her early twenties, she worked as a servant in Skaftafellssýsla, where she bore two children, in 1768 and 1770. She named their father as Sigurður Þorsteinsson, a married farmer from Kotey. Both were fined for adultery, but Arndís alone was exiled from the district.

She returned to her parents’ home, now pregnant with a third child, whom she claimed was fathered by another married farmer, Oddur Eyjólfsson.

At this point, her case took on a greater severity, and she was sentenced to death by drowning under Stóridómur, the long-standing Icelandic law that punished extramarital relations. However, the sentence was overturned, and instead, she was sent to prison at Arnarhóll in Reykjavík.

During her time in prison, she bore two more children, this time fathered by her fellow inmate, the outlaw Arnes Pálsson, a known associate of Fjalla-Eyvindur.

Exile and Forced Labor

After serving four years in prison, Arndís was released—pregnant once again. This time, the father was Ari Pétursson, an unmarried fisherman from the north, who had been working near Arnarhóll.

She returned to her family, but authorities soon banished her from the southern quarter of Iceland.

By 1780, she had settled in Hafnarfjörður, where she entered into service at Hvaleyrarkot and bore two more children with her employer, Nikulás Bárðarson. Though their relationship appears to have been affectionate, the authorities intervened, separating them.

Having now borne eight children without marrying, she was once again brought before the courts. This time, the governor demanded her execution, though the courts instead sentenced her to lifelong forced labor in the Copenhagen spinning house.

An Unexpected Reprieve

As her case moved toward its final resolution, a widower named Magnús Pálsson stepped forward, offering to marry her. A petition for royal clemency was submitted, and her sentence was overturned.

However, before the matter could be settled, Magnús died. The authorities, now unsure of how to proceed, abandoned the case, and after 20 years of legal proceedings, they let the matter rest.

A Quiet End

By 1788, Arndís had married Jón Jónsson of Eiðar in Mosfellssveit, and they had one daughter together. Jón died young, and from that point on, Arndís faded from historical records.

She passed away in 1806.

A Woman Who Would Not Be Broken

In his account of her life, Guðni Jónsson reflected on how Arndís’ story might have been different if not for the brutal double standards of the time. He wrote:

“There is no physical description of Arndís Jónsdóttir. But there can be no doubt that she must have possessed great attractiveness. Nowhere in the court records is there any suggestion that she lacked intelligence or understanding. In fact, she always answered questions firmly and clearly. Everything indicates that she was in no way inferior to the other women of her time, neither in intellect nor in appearance. Had she married young, her life would likely have been no different from that of any other woman of her era, and her name would have simply been another in a respectable genealogy.”

Concealed Births and Infanticide in Iceland

In historical Icelandic law, “dulsmál” referred to criminal cases where a woman secretly gave birth and either killed or abandoned the child—sometimes with the knowledge or assistance of the father or others. A striking example of such a case was reported in the Icelandic newspaper Ísafold in 1874:

A Case of Concealed Birth (Excerpt from Ísafold, 1874)

At a farm near Reykjavík, a 19-year-old girl, the foster daughter of the farmer, gave birth in secret and then murdered the infant in a gruesome manner.

It happened during the autumn sheep round-ups when the girl complained of stomach pains and took to her bed. She claimed it was a condition she often suffered from and did not raise suspicion. However, the pain was in fact labour contractions, and she delivered the child alone in bed, unnoticed by the household, despite people walking in and out of the room. According to her later confession, the baby cried at birth.

She then took a self-feeding knife (a folding knife she owned) and stabbed the infant to death. She hid the body under her pillow until the following morning, acting as if nothing had happened. Although some bloodstains were noticed on her clothes and bed, she dismissed concerns, claiming she had experienced sudden menstrual bleeding. She further explained away her recently swollen appearance, stating that it had been caused by the same condition but had now disappeared. She had also dressed carefully to conceal any physical changes, so few had noticed anything unusual.

A month later, rumours of infanticide at Sauðagerði began to spread, though no one knew the source. Authorities launched an investigation, and the truth eventually surfaced.

When questioned, the girl led investigators to the body of her child. She had left it near the edge of a peat-cutting trench, partially submerged in water, with a few clumps of peat covering it. Upon examination, the body bore eight stab wounds, including two directly to the heart.

— Ísafold, 14 November 1874

Stóridómur – Iceland’s Grand Judgement

Few laws contributed more to the darker side of Icelandic history than Stóridómur (The Grand Judgement). Passed by Alþingi in 1564, this strict legal code governed moral conduct and led to harsh punishments for those who violated it. The law was drafted by Páll Vigfússon and Eggert Hannesson, two prominent lawmen, following encouragement from Páll Stígsson, the royal governor of Iceland. It was officially signed into law on 30 June 1564 and later confirmed by the Danish king on 13 April 1565.

The purpose of Stóridómur was to establish clear legal guidelines for handling cases of immorality, which had previously fallen under the authority of the Catholic Church before the Reformation. However, instead of a standardized judicial system, the result was a dramatic increase in severity, particularly for incest, which became a capital offense. Adultery was punishable by heavy fines, and a third offense carried the penalty of death, though this was consistently commuted to exile. Illegitimate childbirth, including concealed pregnancies (dulsmál), also resulted in substantial financial penalties.

Under this law, sheriffs were tasked with conducting investigations, prosecuting offenders, and collecting fines.

50 People Excecuted for Incest

In total, 50 people—25 men and 25 women—were executed for incest under Stóridómur. The last recorded execution under these laws took place in 1763. By the late 18th century, the enforcement of these strict moral laws had begun to soften, as concerns arose about the economic burden of supporting destitute children and impoverished individuals. The fines for illegitimate births were abolished in 1812, and other moral statutes were gradually repealed.

Despite these changes, Stóridómur remained technically in force for over 300 years, only being formally removed from Icelandic law in 1870, when Denmark introduced a new criminal code, marking the end of its legal authority.

In Modern Times

Iceland has been ranked the world’s safest country for 15 years in a row, but that doesn’t mean it is, or ever was, free of crime. The darker side of Icelandic history tells a different story—one of harsh laws, infamous criminals, and punishments that often blurred the line between justice and cruelty. From executions at Drekkingarhylur, where women were drowned for so-called moral crimes, to the brutal massacre of Basque whalers, the past is filled with grim reminders of a time when law and order were often ruthless.

Though Iceland today enjoys low crime rates, crime still exists, and history shows how justice has evolved—sometimes for the better, sometimes in ways that still raise questions. The echoes of this past remain in folklore, historical sites, and preserved records, offering both a fascinating and sobering glimpse into Iceland’s more brutal history.

Please signup for our newsletter for more fun facts and information about Iceland.

The post The Darker Side of Icelandic History appeared first on Your Friend in Reykjavik.

vigna

vigna